Pratt Center

Pratt Center News - Winter 2008

In this Issue:

- A Message from Pratt Center Director Brad Lander

- Supporting Small Retailers

- Connecting Congestion Pricing and Transportation Equity

- Meet the Pratt Center Staff: Wendy Fleischer

- Building a Balanced Sunset Park

- City Adopts Community Plan for West Harlem

- Introducing The Eminent Domain

- One City/One Future Sparks Discussion

- We're 45! Please Support the Pratt Center

A Speedy Ride for All

A Message from Pratt Center Director Brad Lander

The Bloomberg Administration's proposal for congestion pricing has provoked such intense backlash from a few loud voices you'd think most New Yorkers had something to lose by charging vehicles to enter mid- and lower Manhattan during business hours. On the contrary, we've got everything to gain.

Fewer than 3 percent of workers in Brooklyn, 4 percent in the Bronx and Manhattan, 5 percent in Queens and 7 percent in Staten Island would have to pay a congestion pricing fee in order to get to work, according to research from the Pratt Center's Transportation Equity Project and the Tri-State Transportation Commission. And the vast majority of the very small percentage who do drive into lower Manhattan are well-off, with a median annual household income of $97,136 according to the IBO.

One critical question, though, is how to use those fees on private vehicles to make our mass transit system work for those who are currently worst-served by it. And that's where the Mayor's transportation vision still needs some serious work. PlaNYC 2030 projects $380 million in net revenue in the first year of congestion pricing, rising to $900 million annually by 2030. The Bloomberg administration rightly commits to use that money to pay for an expansion of mass transit. But of the $50 billion in transportation expansion plans currently in the works, only about $1 billion would be devoted to creating new mass-transit service for those who currently endure the longest commutes.

That is way too little. New research from the Pratt Center's Transportation Equity Project -- led by Joan Byron and Elena Conte -- shows that more than 750,000 New York City residents are "extreme commuters," commuting an hour or more to work, each way. Two-thirds of these riders make less than $35,000 a year. A subway system that effectively stopped expanding in the 1930s is failing to serve entire swaths of the city, from East Flatbush to East Elmhurst to Soundview, that are off its grid. Even some areas that have subway service, like Flushing and Washington Heights, are home to thousands of these low-wage extreme commuters -- because our rapid-transit system is totally focused on getting riders to and from Manhattan, while these passengers' jobs are elsewhere.

The MTA and NYC Department of Transportation are now looking to Bus Rapid Transit service, or BRT -- buses that get their own lanes, with fares collected at sheltered stations -- to get passengers to where they're going, fast. Think of a bus that runs like a subway train, but on the street. BRT makes a whole lot of sense for New York City. Compared to subways, a BRT system doesn't cost much to build or operate, or require disruptive construction. But current plans call for just five BRT routes initially, that don't take people into Manhattan, and don't have sheltered stations. And the MTA has refused to commit to a timetable for their launch.

As the state legislature moves to decide how New York City will reduce its increasingly intolerable traffic, we've got a precious opportunity to make sure every New Yorker has a swift and affordable commute to work. Recognizing this, community, environmental justice and civic groups around the city have come together in a new coalition, Communities United for Transportation Equity (COMMUTE)., to press for congestion pricing and Bus Rapid Transit. You can read below about the Pratt Center's work in support of COMMUTE, and our revealing findings about New York City's long-haul transit riders, who are much more likely to be black or Latino than white. Looking at the facts, and being collectively ambitious about creating a sustainable future, New York can resume building a mass transit system that sustains a prosperous, green and livable city.

Equitable Development Policy

Supporting Small Retailers

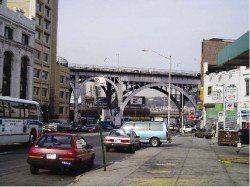

Photo by Wally Gobetz

In response to mounting concern over the growing dominance of chain retailers in New York City neighborhoods, the Pratt Center has begun exploring strategies for supporting and sustaining independent businesses. A November presentation by Pratt Center Director of Planning and Preservation Vicki Weiner on a panel at the Municipal Art Society on strategies to preserve small retail prompted the East Village Community Council to contact the Pratt Center for assistance in developing a retail strategy for the East Side of Manhattan north of Houston and south of 14th Street.

Weiner and students at Pratt Institute's Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment are now conducting a study of the area between 6th and 10th streets, from First to Third Avenues, to assess the current mix of retail and recommend strategies to promote businesses that serve the neighborhood and are true to the East Village's diverse and eclectic character. The course, which Weiner is co-teaching with Jonathan Martin, consists of two studio classes working jointly: one in land use planning and the other in historic preservation, allowing students to creatively combine elements of each discipline in pursuing solutions to the complex challenge of sustaining small-scale retail.

The strategies Weiner and her students are evaluating include restrictions on "formula retail" -- businesses operating more than a certain number of stores -- a strategy that is already in place in San Francisco. They are also examining the potential of supports, such as tax incentives targeting locally owned small businesses that add to neighborhood quality of life. Another strategy under study is commercial rent control. New York City had commercial rent control in place from 1946 to 1963; an attempt to revive it in 1987 was unsuccessful.

To learn more about these and other strategies for promoting local retail, download the Pratt Center presentation Preserving Local Retail: Issues and Strategies.

Sustainability and Environmental Justice

Connecting Congestion Pricing and Transportation Equity

In December, Pratt Center's Transportation Equity Project brought together leaders from a dozen organizations around the city whose constituents suffer the double whammy of poor transit access and limited economic opportunity, to explore opportunities to improve transit access for underserved New Yorkers. At the Transportation Equity Summit, environmental justice and community organizing groups compared riders' stories of hour-plus commutes to low-wage jobs, and identified travel within boroughs as an especially underdeveloped part of the city public transit system.

Participating groups, which included UPROSE, Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice, Sustainable South Bronx, Catholic Charities (Queens), and Queens Community House, examined benefits of congestion pricing for low-income communities -- those inherent in reducing auto traffic, as well as potential gains if funds generated through congestion pricing can be dedicated to transit improvements for areas with the poorest service and greatest need for investment.

The Transportation Equity Summit became the launching pad for Communities United for Transportation Equity, COMMUTE., a new coalition advocating for mass-transit investments to improve the speed and reliability of rides for the New Yorkers who most urgently need improvements. To support COMMUTE's advocacy, Pratt Center's Joan Byron and Elena Conte generated research and maps showing alarming inequities in New Yorkers' access to reliable mass transit. Of the New Yorkers who ride more than an hour each way to work, two-thirds make less than $35,000 a year, while just 6 percent make more than $75,000. Commuters are also divided by race. Black riders, on average, have rides that are 25 percent longer than those of white riders; Hispanic passengers typically have rides that are 12 percent longer. At a January hearing of the New York City Traffic Mitigation Commission, COMMUTE members used these and other Pratt Center findings to advocate for congestion pricing and Bus Rapid Transit.

For more information on the Transportation Equity Project, contact Elena Conte, econte@pratt.edu or 718-399-4416.

Sustainability and Environmental Justice

Meet the Pratt Center Staff: Wendy Fleischer

Wendy Fleischer is new to the Pratt Center's staff, but you wouldn't know that from her contributions here. Over the last year, Wendy developed the ABCs of Community Development training for staff, board members, and volunteers of neighborhood nonprofits and wrote the grant proposal that supports a new Pratt Institute program to integrate environmental sustainability throughout the academic curriculum. This winter, Wendy joined the Pratt Center full-time as our new Sustainability Project Manager and NYSERDA Energy $mart Communities Coordinator.

NYSERDA is the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority, which has retained the Pratt Center to promote energy efficiency and sustainable building and management practices. Fleischer is working on strategies to help affordable housing developers and managers retrofit buildings to be greener, healthier and more financially viable.

Fleischer previously worked as a program developer and writer for foundations and nonprofits, working on community and workforce development, community organizing, justice reinvestment, after-school programs, and supportive housing for groups including the Corporation for Supportive Housing and the Fifth Avenue Committee. She has a Masters degree in City and Regional Planning from the University of Pennsylvania and participated in the Revson Fellowship for the Future of the City of New York.

The possibilities of integrating her experience working in community development with steps to address the crisis of global warming inspired Fleischer to take on the challenge of getting buildings to go green. "Personally it had a lot to do with me having a child, and not being able to look at him and say, 'By the time you grow up, there aren't going to be polar bears and half the species on the planet are going to be extinct.'"

She is currently working on resource guides and training for affordable housing building managers, informing them of funds and programs they can turn to improve energy efficiency -- saving buildings and their residents money in the long run. Her work will also focus on contractors. She is ensuring that contractors are aware of training opportunities and incentives to meet the increasing demand for building energy retrofits. She sees the need to develop a new building auditor trade as an opportunity to enhance the capacity of minority- and women-owned firms and workers. "By doing this work in affordable housing, we can make it greener healthier, better for the planet, more enduring, less expensive to run, and create jobs too," says Fleischer. "It's my job to try to make that easy."

Community Planning

Building a Balanced Sunset Park

Residents of Sunset Park, Brooklyn could have been satisfied by their successful fight against one developer's plans to construct a twelve-story building that would have marred the view from the neighborhood's namesake park. But following their effective but exhausting lobbying campaign, they recognized that instead of fighting out-of-scale development one building at a time, there was a larger need for a rezoning of the entire neighborhood, where new development currently faces no height restrictions.

The Pratt Center worked with Councilwoman Sara Gonzalez and Community Board 7 to help Sunset Park's residents weigh in on current development and a potential rezoning. At a town meeting in March, Mayor Bloomberg and the NYC Department of City Planning agreed to conduct a zoning study of Sunset Park. In order to gather residents' input into the rezoning process, the Pratt Center worked with CB7 and Councilwoman Gonzalez to convene a series of community workshops in the fall of 2007. After an initial presentation introducing residents to basic zoning principles, subsequent workshops featured small-group discussions of concerns and priorities surrounding new development, where new development should and should not occur, and strategies for creating and preserving affordable housing.

Community members were united in their goals to prevent out-of-scale development, preserve and create affordable housing, protect the view from Sunset Park, a neighborhood treasure, and prohibit commercial zoning overlays on residential streets. However, opinions varied on the best way to achieve the preservation and creation of affordable housing. Some residents supported the idea of additional density on one or more of the neighborhood's commercial avenues to generate affordable housing. Other residents and community organizations, however, feared that upzoning avenues that include rent-stabilized housing might displace low-income residents and eliminate more affordable housing than it would create.

As City Planning works on its study and considers possible future zoning actions, the Pratt Center's work educating Sunset Park residents about the benefits and trade-offs of different zoning strategies has enhanced the community's knowledge base and set the stage for an informed public process to shape the neighborhood's future.

For an in-depth look at the Pratt Center's findings, download our report: Sunset Park Voices in the Rezoning Process.

Community Planning

City Adopts Community Plan for West Harlem

The City Planning Commission and City Council have approved a "197-a" plan for West Harlem, a community-crafted vision for the area created by Community Board 9 under the guidance of the Pratt Center and the Harlem Community Development Corporation. The adoption of the community plan was overshadowed by the simultaneous City approval of Columbia University's own request to rezone 17 blocks of Manhattanville, which is part of CB9, for the expansion of its campus.

In backing the Columbia expansion plan the City declined to adopt the community recommendations for Manhattanville, which centered on preserving space for light industry alongside Columbia's institutional buildings. The City's action was a deep disappointment for CB9, which had worked intensively on the community plan for four years and felt that the community's point of view should have had far more weight in determining the future of the neighborhood. However, some recommendations in the community plan are now influencing Columbia's and the City's actions.

The CB9 plan recommended the creation of the West Harlem Local Development Corporation to negotiate for community benefits with developers. As the university expansion plan went before the City Council, Columbia and the LDC reached an agreement committing the university to finance new public school, an affordable housing loan fund, legal services for West Harlem tenants, and other resources, pledges Columbia values at $150 million.

In approving the 197-a plan, the City Planning Commission endorsed of a number of the community board's recommendations, including protecting the view to the Hudson River at 125th Street; preservation of manufacturing west of 12th Avenue; reuse of abandoned sites; a park and bike path along the river; reuse of a former marine waste transfer station; and creation of a community land trust. Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer incorporated many of the 197-a plan's recommendations -- including contextual zoning to restrain out-of-scale-development in West Harlem and inclusionary zoning to create affordable housing in new development -- in his own proposal for a "West Harlem Special District" covering the areas adjoining Columbia's expansion area. The Department of City Planning is now considering zoning changes related to Stringer's and the Community Board's plans.

Equitable Development Policy

Introducing The Eminent Domain

This winter, the Pratt Center is launching a news and information website connecting New Yorkers who are working to make major real estate and economic development projects responsive to the needs of communities they're being built in. The Eminent Domain is beginning by chronicling plans for three areas -- West Harlem, Kingsbridge, and downtown Brooklyn -- in partnership with groups that are organizing neighborhood residents to have a say in how development proceeds. The site will also be reporting on projects elsewhere in the New York region, and nationally, of interest to citizens and organizers working to promote accountable development.

In downtown Brooklyn, Families United for Racial and Economic Equality (FUREE) will be reporting on its members' work pressing for affordable housing, living wage jobs, community spaces, and other resources for longtime area residents as the area undergoes a boom in luxury residential and retail development. In Kingsbridge, the Bronx, the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition will track its efforts to secure a community benefits agreement, and especially living wage, union jobs, tied to the redevelopment of the Kingsbridge Armory. And in West Harlem, Community Board 9 is working to see through the vision laid out in its 197-a plan recently approved by the City Planning Commission (see above), as the City moves forward on rezoning plans for 125th Street and other parts of the area.

The Eminent Domain also includes ongoing analysis from Editor Alyssa Katz, formerly editor of the magazine City Limits (and author of this newsletter), with reporting from students in the Department of Journalism at New York University.

Equitable Development Policy

One City/One Future Sparks Discussion

Following months of intensive work on a draft blueprint for economic development in New York City, in late November the civic, community, and labor organizations collaborating on One City/One Future took the proposals public for the first time at a late November event at the Murphy Institute for Labor, Community and Policy Studies of the City University of New York. Nearly 150 participants packed the forum and participated in discussion groups giving feedback on the blueprint and its proposals. The draft report recommended 40 policies grouped into three areas of action: Invest for shared growth; Set higher standards; Reform the process. Read more about the event here.

New York Jobs with Justice, the Pratt Center for Community Development, and the Brennan Center for Justice convened One City/One Future to engage advocacy groups throughout New York City around a set of principles and policy recommendations that ensure that development in New York City advances economic opportunity and builds diverse and sustainable neighborhoods. Since the project's inception, hundreds of advocates, organizers and scholars have contributed to the forthcoming blueprint. A series of workshops generated a set of six principles for economic development. Throughout 2007, working groups examined policies affecting housing, jobs, workforce development, the environment, economic security and social infrastructure in New York City.

For more information on One City/One Future, contact Sadaf Khatri at NY Jobs with Justice, sadaf@nyjwj.org.

Support the Pratt Center!

1960s: We collaborated to create the community development corporation model

1970s: We taught neighborhood groups and homesteaders how to rehabilitate abandoned buildings

1980s: We assessed and addressed the impact of Reagan Administration policies on New Yorkers and our neighborhoods

1990s: We helped New York City's environmental justice and small schools movements take flight

2000s: We brought new affordable housing strategies to an increasingly expensive city

What comes next? Help make it happen.

On February 26, the Pratt Center for Community Development will be celebrating our 45th Anniversary with a gala event at Gotham Hall, on Broadway at 36th Street in Manhattan. In our more than four decades of service to New York City, we have helped community organizations create and preserve affordable housing; revitalized neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs; moved public policy to build power for New Yorkers and their communities; created child care and community centers; and promoted social, racial, economic and environmental justice through innovation in planning and advocacy.

We'll be honoring three New Yorkers who have made extraordinary contributions to further those goals: Alexie Torres-Fleming, founder and executive director of Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice; Jonathan Rose, founder of Jonathan Rose Companies and a leading affordable housing developer; and architect J. Max Bond, a partner in Davis Brody Bond Architects and Planners, where he is currently supervising the firm's work on the World Trade Center memorial and museum.

To purchase tickets, contact Margaret Fox at 718-636-3486 x6462.