Pratt Center

Toward an Informed Rebuilding: Documenting Sandy's Impacts

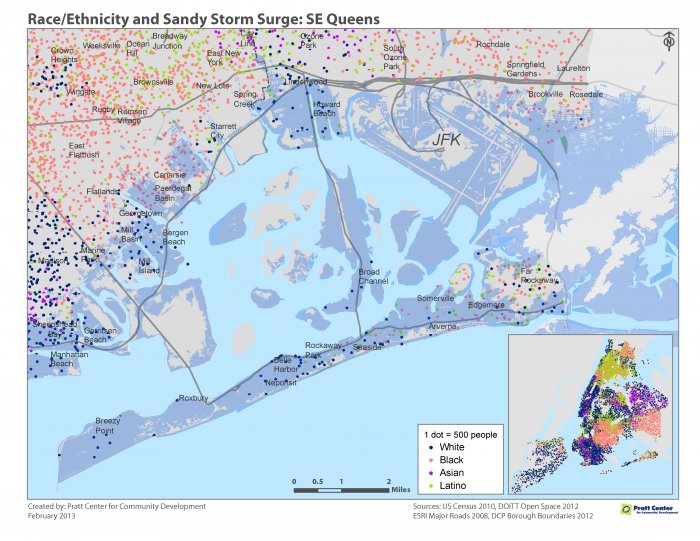

Hurricane Sandy exposed not only the urgent need for resiliency planning across New York City, but the disparate impact of climate change on low- and moderate-income communities and small businesses along the city’s waterfront. From the NYCHA tenants living without electricity and gas for months to the Brooklyn Navy Yard manufacturers whose equipment and inventory were destroyed, the storm overwhelmingly affected New Yorkers without the economic, technical and political resources to quickly respond and recover. In several low-income communities of color, over 90% of housing units – tens of thousands of homes – were damaged or destroyed. Communities in the Rockaways, Red Hook and Coney Island were already struggling with an inadequate and poorly maintained physical infrastructure, economic isolation, high foreclosure rates and housing in disrepair – injustices exacerbated by the storm.

As communities, businesses and government begin the long process of rebuilding and planning for resiliency, it’s imperative that they have comprehensive information on the storm’s impacts as they determine zoning, building code, construction, remediation and funding priorities. Unfortunately, there is still limited public information on the extent of the damage done, or other key data, such as the number of people living in the flood zone.

Pratt Center has begun to document the impact of the storm through a series of maps focusing on residential areas and Industrial Business Zones (IBZs) devastated by Sandy. You can access the full series of maps here. The residential maps document the number of homes directly affected in Coney Island and the Rockaways, and show how vulnerable many residential neighborhoods remain to future storms. The NYCHA map, in particular, illustrates the storm’s disparate impacts on low-income New Yorkers. The IBZ map demonstrates that many industrial areas, including those which use or store toxic materials, are also located in low-lying waterfront areas. There is a concern that toxics were carried by the floodwaters into surrounding residential areas and deposited in the soil.

These maps are just a start. We need more comprehensive data that accounts for the damage done to residential and industrial communities to enable all New Yorkers to understand the challenges we face, as well as to inform the equitable allocation of rebuilding funds.